Unfolding Worlds – part 1

Jean-Marie Bytebier & Elger Esser & Tinus Vermeersch

Brussels

13.03 - 30.04.2022

Works

Installation views

Press release

UNFOLDING WORLDS

The lyrical landscapes of Jean-Marie Bytebier, Elger Esser and Tinus Vermeersch.

Part 1 from 13.03 – 30.04.2022

Dear visitor,

It is not really the custom to address the visitor directly in the accompanying text of an exhibition. There are many ways to familiarise the viewer with the art on view in a venue text, but generally, a neutral, objectifying style is chosen.

I am sorry to be making an exception to introduce you to the exhibition ‘Unfolding Worlds’ featuring the landscapes of Jean-Marie Bytebier, Elger Esser and Tinus Vermeersch, but you will understand that my decision to opt for a more personal and subjective tone in writing this text has to do both with the style, which is simply the easiest for me, and with the choice of works that the gallery owners have brought together here.

This personal way of writing allows me to confess my absolute love of these three artists’ lyrical landscapes and to focus on a more theoretical and art historical point I would like to make.

It’s not that I want to overwhelm you with theoretical concepts and arguments based on my authority as a doctored art historian on the representation of the Flemish landscape in contemporary art (see: ‘Way of Flanders’ 2013) in order to increase the artistic value of the landscapes shown, nor because I assume that when these works of art are theoretically underpinned you must accept my subjectivity as an objective fact. Rather, I am very curious about your own personal aesthetic experience.

In short, I love the landscapes shown here and ask myself whether you, as a visitor, share that love or not? And why or why not? Let’s start this imaginary dialogue from a distance and begin with the resident Hopstreet artist Tinus Vermeersch, for whom the ‘imaginary landscape’ occupies such an important place.

Tinus Vermeersch (b. 1976) is a ‘Belgian Archaist’, an artist who has applied the literary technique of ‘a conscious imitation or adoption of style, words, phrases or expressions belonging to a certain period’ to the visual arts.

His works look as if they could have been made in the 16th, 17th, 18th or even 19th century (think of the heavenly landscape paintings by Roeland Savery, the landscape etchings by Hiëronymus Cock, or the Ghent etchings by Jules De Bruycker) because their tiny, delicate movements of a drawing or painting hand and their archaic style bring to life imaginary landscapes with mythical creatures (half-man/half-bird/half-tramp/half-monk) in a time that seems to be out of sync with normal time.

As soon as I see a work by Tinus, I am drawn into a meditative space in which the existential aesthetic experience of the landscape that brings about an interaction between man and landscape (see: Ton Lemaire, ‘the humanisation of the landscape, the landscapeification of humans’), is brought to life – just like with Thierry De Cordier – under the hands of a landscape artist like Tinus Vermeersch. Why else would all his figures disappear into those old haystacks?

Other than in a possible nostalgic reading of his works, Vermeersch does not revert to elements from old Flemish landscape (the haystack) or old Flemish art (Savery, Cock, De Bruycker, etc. paintings/etchings/ceramics/grisailles) to evoke a non-existent glorious Flemish art past, but to evoke the essential link between man and his natural environment at least in art. The security that nature could offer and the mental peace to escape the me-fixation is an artistic antidote — a form of lyricism that has nothing to do with escapism but everything to do with the necessary desire for a new balance between man and nature.

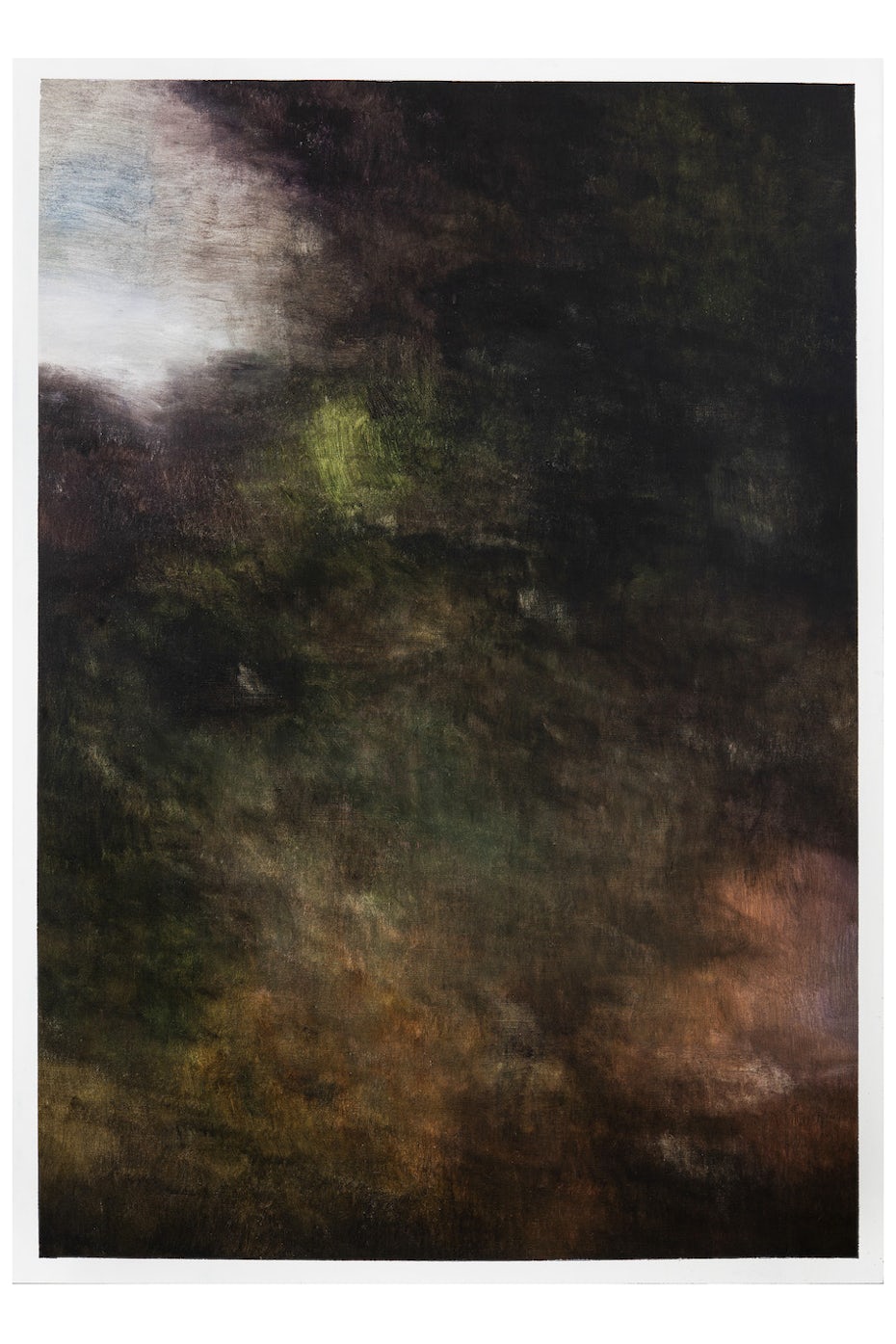

Something similar must have attracted me to the large landscape paintings by

Jean-Marie Bytebier (b. 1963).

I remember vividly how I looked at his landscapes for the first time in his studio in Ghent. I was putting the finishing touches on my book on landscape and was mentally unable to keep an open mind about what I was seeing. I was so stuck in the theoretical framework that I was writing until two things happened, and I was able to take the large, brown, atmospheric landscape paintings with their broad white frames, in which one bright spot often breaks through the darkness at the top, fully into my heart.

The first time was when I was able to admire one of Bytebier’s large landscape paintings in the Museum in Ixelles at the ‘Belgian landscapes’ exhibition and compare it with a dark seascape by Thierry De Cordier. The second time was when, in the middle of summer in my city garden, I tilted back my deck chair and saw the sky appear above the green of the leaves of the trees.

For that is what happens in the ‘atmospheric abstraction’. Bytebier fuses photos taken during walks abroad with reproductions of well-known classical European paintings. Not only does he evoke the atmosphere of a dark forest, a place where the walker is surrounded by trees, he also raises the gaze, enlightens the mind and has an existentially optimistic effect on me by having a ‘Leuchtung’ appear so emphatically and often at the very top of the picture. As optimistic and proud as a ‘zip’ in a ‘colour field’ by Barnett Newman.

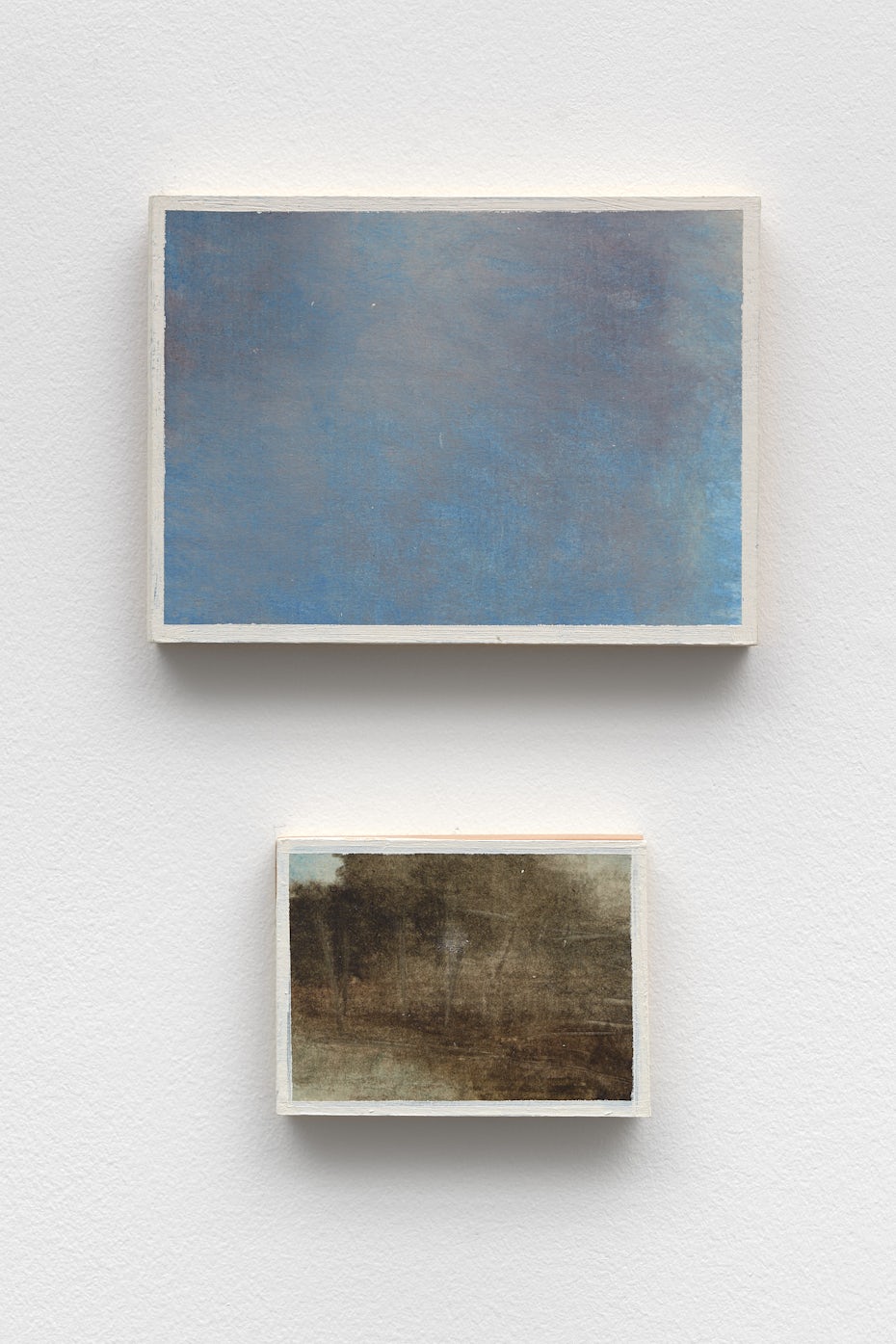

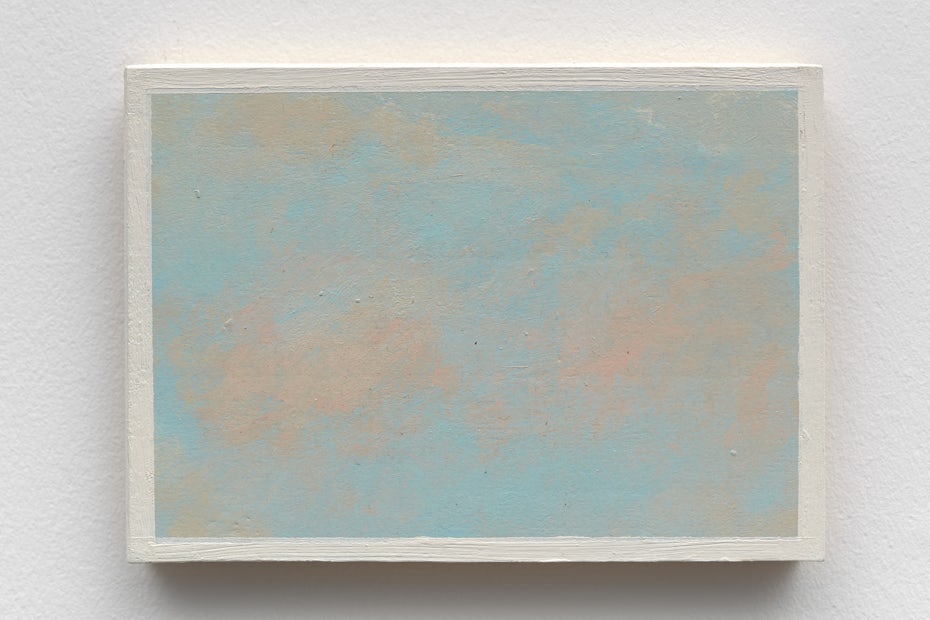

And we have not even mentioned the exceptional position of the photographer

Elger Esser (b. 1967). Because of his training, he was once classified among the ‘Becher School’, but he has nothing in common with the pupils of Bernd and Hilla Becher. They all portray the landscape in the same detached, cold, topographic manner. While those Becher photographers create ‘unattainable landscapes’ from an ‘unembodied gaze’, Esser, a German who grew up in France and constantly sings the praises of the French landscape in his photographs, does the opposite.

The typical white skies in his pictures, produced by the old photographic technique he uses (heliogravure), combined with the magical moment of a sunset (the disappearance of natural light), cut the image out of existing time while giving the viewer access to the landscapes he portrayed in a vast, welcoming gesture. It returns a sacredness to the landscape and nature, a form of awe for the original beauty, and a perfect antidote to all the other catastrophic landscapes in contemporary art, which, out of real climate angst, cut us off emotionally and mentally from the natural landscape once again.

For me, it is clear that these three landscape artists are part of a broader artistic movement in which there is a ‘return of the lyrical landscape’ after ‘the end of the lyrical landscape’. That’s why I love it so much, but listen to what your inner aesthetic voice is telling you. I am very curious to know how you experience these landscapes.

Jeroen Laureyns of the Agentschap voor Geestelijke Gastarbeid, de Belgische Sectie.