The Emergence of Memory

Thorsten Brinkmann & Elina Brotherus & Sara Imloul

Brussels

12.01 - 01.03.2025

Works

Installation views

Press release

The Emergence of Memory [1]

When discussing memory, a distinction is often made between collective and personal memory. However, according to Michael Rothberg, this remembering occurs simultaneously at the collective and individual levels in human beings. Present and past, here and elsewhere, the personal and the collective converge and influence each other. He believes these anachronistic qualities are the source of creativity and the possibility of creating new worlds from the material of past worlds. Moreover, memory is essential for the formation of our identity, which is determined by the interaction of personal memories with other memories, such as those from collective memory. [2]

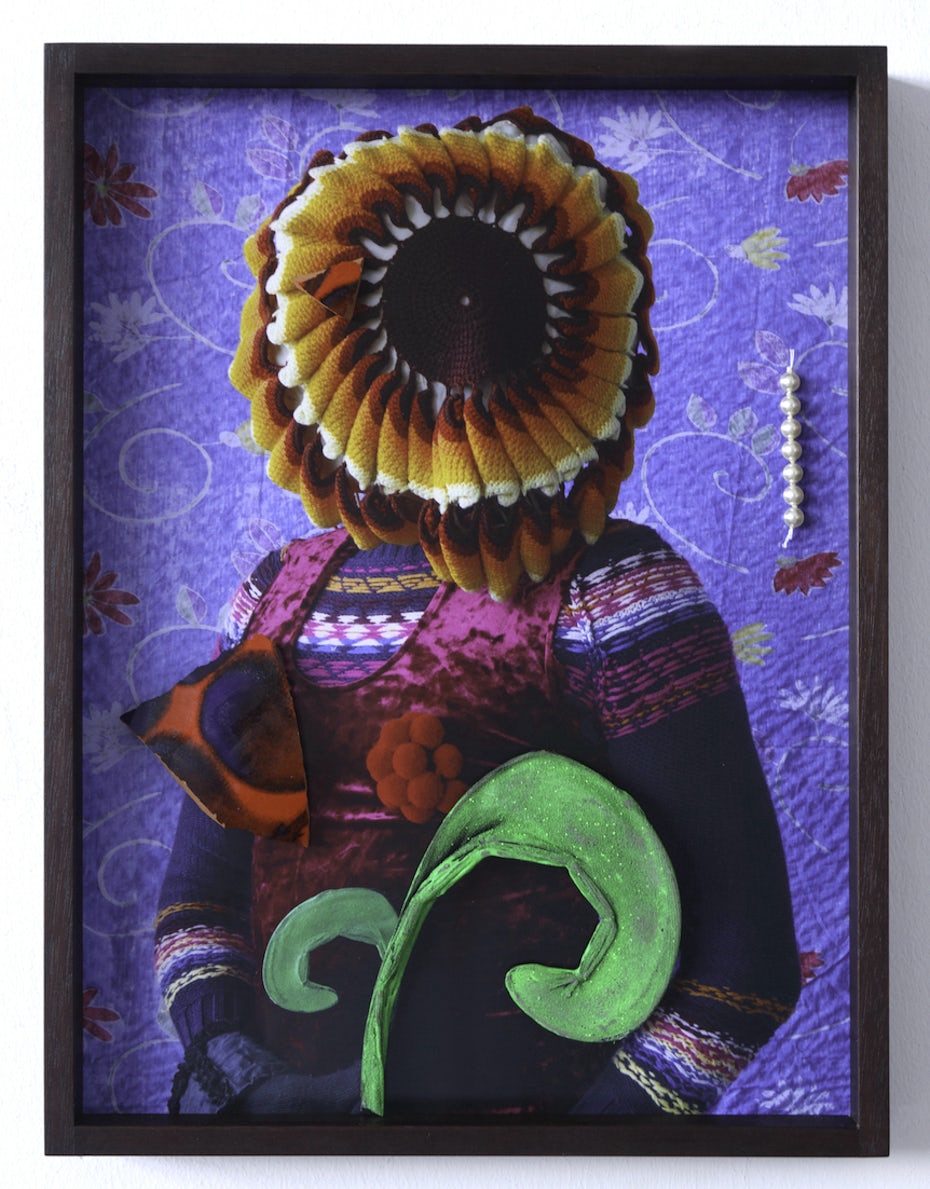

That collective memory helps shape our identity is reflected in the work of Thorsten Brinkmann (b. 1971, Herne, Germany). In 2018, one of his portraits graced the poster campaign of La Monnaie in Brussels with the slogan Who do you play? In his portraits, he gets into the skin of the leather handbag that dangled from your grandmother’s shoulder at the Sunday market or the antique copper milk jug from your great-grandfather’s barn. In her essay On the Emergence of Memory in Historical Discourse, Kerwin Lee Klein argues that memory no longer belongs solely to the individual but is shaped by a diverse and ever-changing collection of material objects and social practices.

She even speaks of a “materialisation of memory”. [3]

The objects collected and worn by Brinkmann confront us not only with personal memories but also with the history of consumerism. The images show us a shift in the zeitgeist—objects have increasingly become part of collective memory, our personal memories and our identity.

Brinkmann’s portraits not only refer to our personal and collective memory but are also peppered with references to art history. The faces of the figures in these portraits are always veiled, and we are left to guess their identities. Only in the titles does he give us a hint, humorously referring to the monks, counts and nuns who populate the portraits we know from art history. In the same way, his portraits refer to modern adventurers from film and TV history. The colours, poses and light in his work evoke the oeuvre of painters such as Anthony Van Dyck, Titian, Rogier Van der Weyden and Jan Van Eyck. Brinkmann thus plays on our collective image memory.

Elina Brotherus (b. 1972, Helsinki, Finland) also never shows us her face in the three sculptures selected for this exhibition. Instead, she offers us a nod to the oeuvre of some key figures in Western art history. In the piece Portrait Series (Jetty) from the series The Baldessari Assignments (2016 – present), she refers to the work of the American artist John Baldessari, who, in the 1970s, invited his art students to perform a list of playful assignments that would spark their creativity. Brotherus used this list in her teaching and eventually drew inspiration from it. The series pays homage to his oeuvre.

In the piece Tombeau imaginaire 26, Brotherus refers to Caspar David Friedrich’s iconic painting Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer. This photo is part of the Sebaldiana series. Memento Mori (2019), which she worked on during a trip to Corsica. Sebaldiana refers to the German author W.G. Sebald (1944 – 2001), who was working on a book about Corsica before his death. In his literary work, Sebald often incorporated photography, exploring themes such as memory, amnesia and the role the visual image plays in memory.

Memento mori can be freely interpreted as a remembrance of death. It is a common motif throughout the history of art. During her journey through Corsica, Sebald became her guide, and she commemorated her loved ones who had died. She sought out places that radiated beauty and where she would have loved to bury her deceased loved ones.

In this series, we invariably see Brotherus gazing out over the Corsican landscape, absorbed in memories, the beauty of nature and the words of Sebald. As in Caspar David Friedrich’s painting, the landscape becomes a reflection of the state of mind of the observer in the picture.

A contemplative mood is also explored in her Model Studies series. In Model Study 8, Brotherus gazes through a glass sphere at her surroundings. This causes reflections of her face and surroundings to be reflected back at the viewer.

La mémoire de l’eau by Sara Imloul (b. 1986, Mulhouse, France) is inspired by the eponymous theory of immunologist Jacques Benveniste, who claimed in 1988 in the scientific journal Nature that water has a memory and can store information forever.

With this series, Imloul continues to develop upon André Breton’s idea of l’écriture automatique and creates theatrical images inspired by dreams and memories. Imloul’s images form a kind of fictional, surrealist diary and, – like our dreams and memories, – are fragmentary, suggestive and fleeting. She stages this dreamy theatre both in front of the camera and while developing the negative. But she always leaves room for coincidences.

She uses calotype, a photographic process developed by Henri Fox Talbot in 1839, in which a paper negative is used to print a positive image. The structure of the paper negative blurs the contours of the original image and allows you to play with contrasts between light and dark. Imloul manipulates each negative manually during the printing process, mixing drawings and collages with the photographic prints. Her work reflects on identity, memory and collective imagination.

Benveniste’s water theory was almost immediately disproved by his colleagues, as the preconceived tests did not give stable results. According to Marita Sturken, memory is fragmentary, suggestive and impermanent, and it is precisely this instability that offers us the possibility of renewal.[4] In this context, memory, like water in Benveniste’s homoeopathic theories, becomes a kind of healing force. It provides a counter-narrative to history, which is usually characterised by a one-sided perspective. It allows us to avoid having to start over again and again with a clean slate and to create a new story out of the past.

Text by Lara Verlinde

[1] The title of this text refers to Kerwin Lee Klein’s essay On the Emergence of Memory in Historical Discourse and Lynne Sharon Schwartz’s book The Emergence of Memory: Conversations with W.G. Sebald.

[2] Rothberg, Michael (2009). Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Stanford University Press. pp. 1-29

[3] Klein, Kerwin Lee (2000). On the Emergence of Memory in Historical Discourse in Representations. The regents of the University of California. pp. 130

[4] Sturken, Marita (1997). Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering. Berkeley. pp. 3-5, 15-17